The most valuable book in my collection is a copy of Neuromancer published in 1986 by Phantasia Press. Only 375 numbered copies were signed by the author, bound with gold endpapers, in a white cloth slipcase. It’s tough to find but there are two copies on Abebooks right now, one for $6,500, the other for $8,000.

The enduring cultural impact of Neuromancer is a story worth telling. William Gibson’s SF classic will bubble into public consciousness again when Apple TV releases a Neuromancer miniseries late next year – the first film adaptation after decades of abandoned development projects.

Let’s dip into the Sprawl, a world of neon drenched streets, gleaming glass towers, and digital tech conspiracies. It’s a story of sophisticated AIs manipulating human affairs, corporate globalization, and a data-frenzied society. Today it seems more prescient than ever, a vision of the world of 2025 written in 1984 on a manual typewriter by an author who did not own a computer.

The story & writing style

Neuromancer tells the story of Case, a down-on-his-luck data thief in the Matrix. Case jacks into cyberspace to make his way past ICE (defensive software barriers), interacting with digital constructs (copies of a person’s consciousness), and hacking his way to an unthinkably powerful artificial intelligence that seeks to become sentient.

(We’ll come back to that summary later. It’s got five important clues hidden in it.)

It’s a high-stakes heist thriller with street samurai and shadowy corporate forces, pulsing with danger and dark beauty. It’s breathtakingly fun and beautifully strange.

It’s also notoriously difficult to read.

When I was a wee lad in my 30s, I started Neuromancer and read a hundred pages or so before bailing out, overwhelmed by the dense, fragmented prose. I made it further in a second attempt a year later, quitting in frustration at the halfway point.

I finished it on the third reading, head spinning, bowled over by its brilliance, aware that I would remember reading it for the rest of my life. Some books reward hard work – Blood Meridian, A Clockwork Orange, and Cloud Atlas come to my mind, maybe you have your own. Neuromancer continues to be a favorite that I return to every few years.

Is it worth the effort for you? Good lord, I don’t know, I find you confusing. But maybe you’re willing to take a chance on a reading experience like no other – and some of you will come out the other side equally changed.

The novel immerses you in a futuristic world without much explanatory exposition, with heavy use of invented jargon and compound words that are visually and conceptually jarring. The plot is intricate and non-linear, with multiple intersecting threads, shifting perspectives, and abrupt scene transitions.

Apologies if I’m making it sound difficult. It’s just a science fiction thriller. But go into it with reasonable expectations – I don’t want you to pack it next to a Sarah Maas romantasy for the next beach vacation.

Cultural impact

Neuromancer was released in 1984. The first personal computers were being lugged around by nerds like me, but William Gibson didn’t have one. There was no internet, no one was online in the way we understand it today.

But look again at the summary of the book above. It’s no accident that so many terms in it look familiar.

Much of the story takes place in cyberspace. Gibson invented the word. It’s the first of many terms and concepts from Neuromancer that were absorbed into our culture.

The Matrix is the virtual reality world experienced by hackers in cyberspace. Neuromancer was a direct inspiration for the Matrix movies. Trinity, the badass Matrix hacker, is a loving homage to Molly in Neuromancer.

Case jacks in to cyberspace. That’s now the standard shorthand term whenever you see an anime, movie, or game character connect their brains to a virtual network or digital avatar.

Defensive software protecting a network is commonly called ICE today, in the real world as well as hacking-related games or shows.

The book describes constructs, digital simulations with the memory and skills of real people. It became a common term and is now used routinely as we interact with AIs that appear to have personalities.

It’s mostly a coincidence but worth noting that Gibson invented mini-software modules plugged into his characters’ brains – and called them microsofts.

Those are specific terms that can be traced directly back to Neuromancer, but its most important impact came in defining the blueprint for cyberpunk, a genre that exploded in the next twenty years and is still influential today. Neuromancer has all the essential elements of cyberpunk: noir-inspired antiheroes, urban decay, omnipresent technology, and virtual worlds.

Gibson didn’t invent cyberpunk. The original Blade Runner film predated Neuromancer by two years and features much of the same aesthetic.

But Neuromancer is widely credited with defining the cyberpunk genre and permanently shaping science fiction and pop culture.

The book gets credit for the look and feel of movies like The Matrix, Ghost In The Shell, Akira, and Robocop. The recent sequel Blade Runner 2049 carries on from the original movie but also owes debts to the world of Neuromancer.

Many cyberpunk-influenced books have been written, most famously Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash. In the 2000s techno-thrillers by Richard Morgan, Paolo Bacigalupi, Daniel Suarez, and Ramez Naam, among others, carry on the cyberpunk legacy.

Cyberpunk games range from Deus Ex and System Shock 2 to the recent ambitious open-world RPG Cyberpunk 2077.

Cyberpunk has inspired musicians – Billy Idol, David Bowie, Sonic Youth. You can find “cyberpunk” playlists on Spotify. Madonna and Lady Gaga adopted cyberpunk visuals for tours. You can find cyberpunk visual art in album covers, game concept art, anime backgrounds, digital paintings, and fashion.

Neuromancer is one of the most honored works of science fiction in the last fifty years. It was the first and only novel to win the holy trinity of science fiction awards – the Nebula, Hugo, and Philip K Dick award. Time Magazine included it on a list of All-Time Best English Language Novels. More than 7 million copies have been sold worldwide.

Although there have been other influential SF works – novels by Philip K Dick, Isaac Asimov’s Foundation and Robot series, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 – I could make a case that Neuromancer is the single most influential SF novel since George Orwell’s 1984.

Publication history & collectible editions

Books by William Gibson have been steadily increasing in value, and Neuromancer in particular seems to hypnotize collectors.

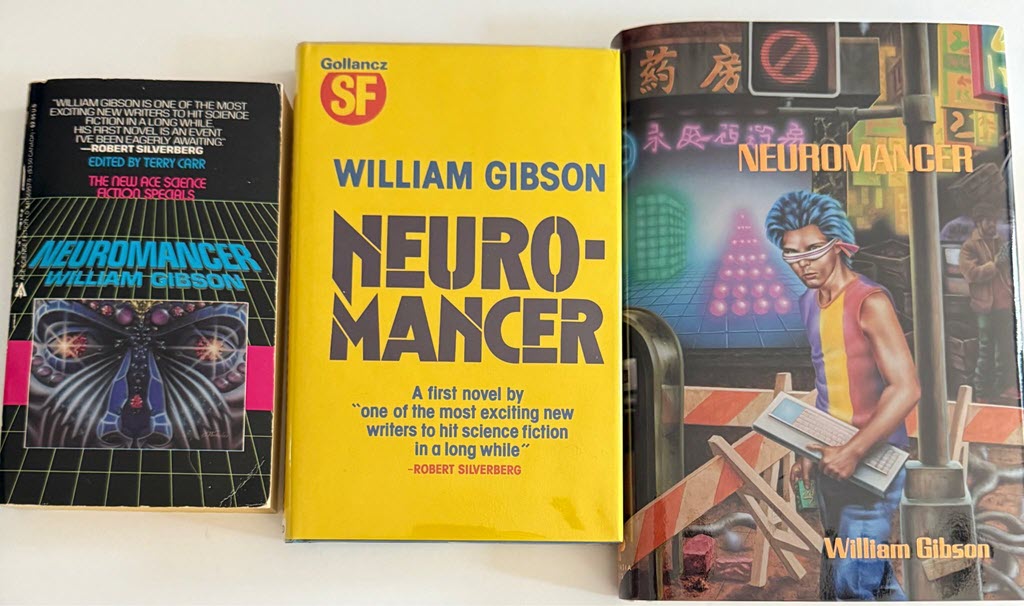

Neuromancer appeared first in paperback – one of the little paperbacks, the kind that used to be sold in drug stores and airports. Those small paperbacks weren’t made to last and today it’s almost impossible to find the first edition in fine condition. Peter Harrington, a well-known London bookseller, has a signed copy for $3,500.

Later in 1984, Gollancz published the first hardcover of Neuromancer. Only 3,000 copies were printed. The scarcity makes it the most expensive release for collectors, even though it’s not attractive or special, just Gollancz’s typical block letters on yellow dustjacket. Expect to pay $9,000 or more for the Gollancz hardcover.

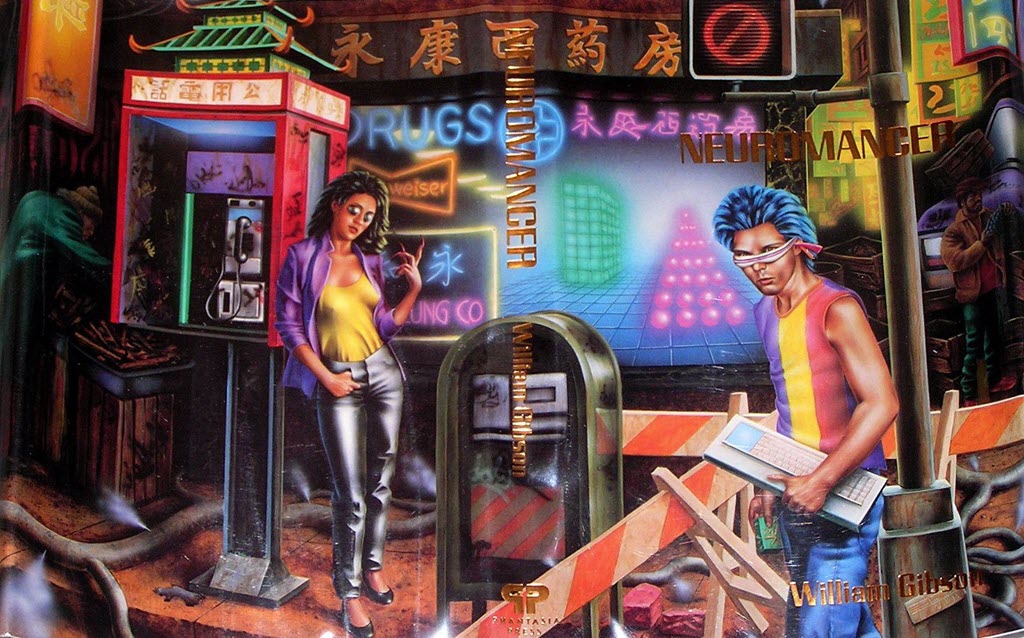

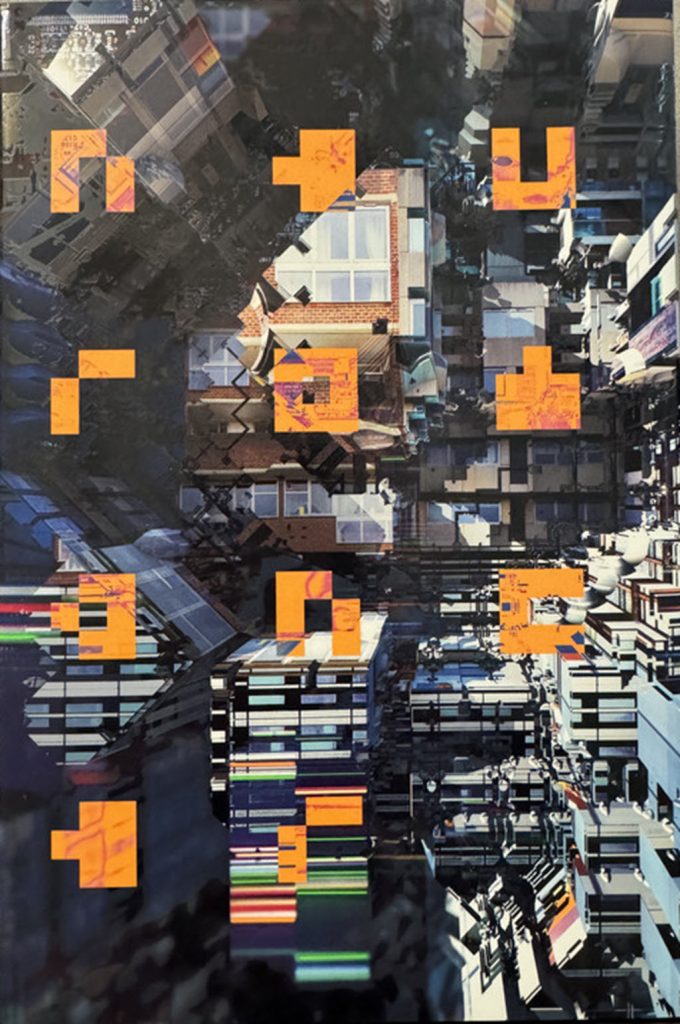

Two years later Phantasia Press released the copy with the dustjacket at the top of this article, with cool artwork by Barclay Shaw, frequently nominated for the Hugo Award for Best Professional Artist. It’s the first US hardcover and the 375 signed limited copies are almost impossible to find. There were also 1200 unsigned copies that are easier to find on Abebooks, typically $2-3,000.

COLLECTORS’ NOTES: Alex Berman, owner of Phantasia Press, posted on Facebook last week: “There were differences in the two states of the book: (1) We used a different “flatter” cloth on the trade edition. (2) where the cover of the s/l edition had WG stamped in gold foil, Gibson’s initials on the trade edition was blind stamped. (3) The end papers on the s/l edition were a heavy gold stock. The trade editions have a beige colored material. We used the same dust jacket for both editions. With $17 as price of trade edition and $45 for the signed/limited.”

Since then Neuromancer has been printed and reprinted. An obsessive collector came up with 112 different worldwide editions as of a couple of years ago. More have been released since then.

There has been a surge of special editions in the last few years.

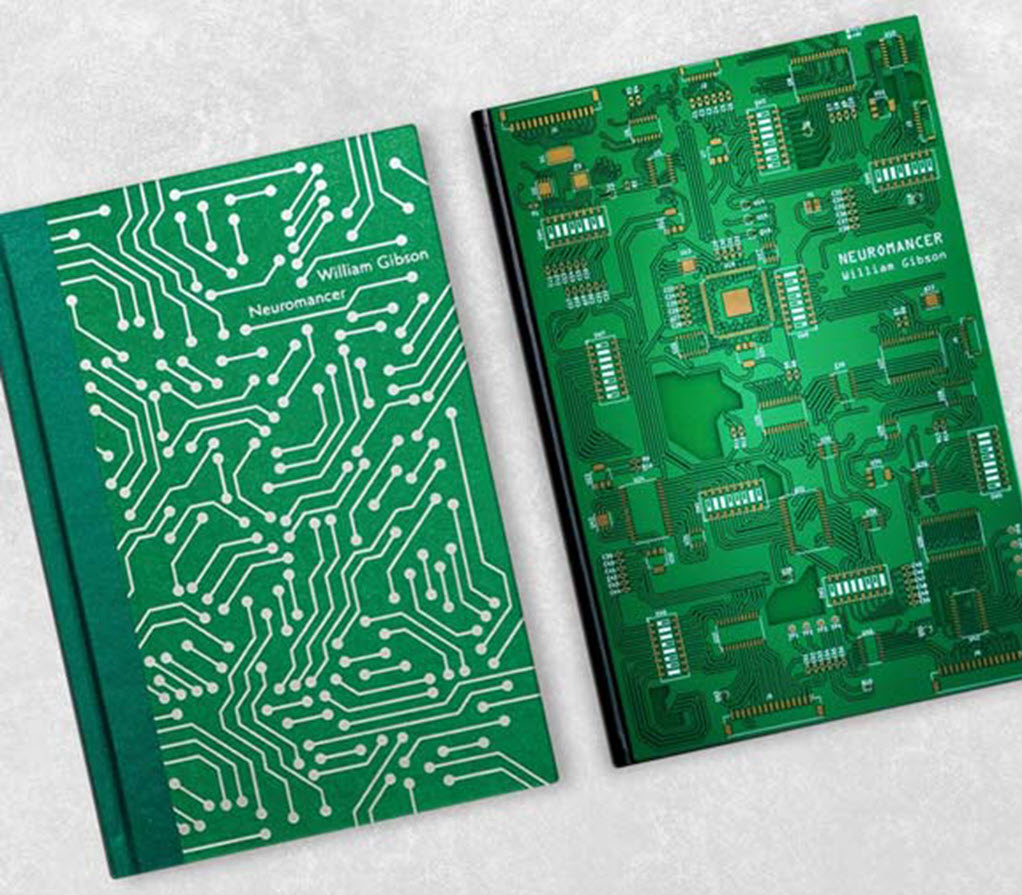

Suntup Press released two particularly beautiful editions, 250 numbered copies and 26 lettered copies. The numbered books have cloth covers that look like circuit boards. The lettered books are bound with actual custom circuit boards for covers.

Last year Gollancz produced 200 signed numbered copies of an edition with new illustrations, housed in a bespoke soft-touch solander box with magnetic-shutting doors – quite striking.

Folio Society released a limited edition last year – 500 numbered copies, 20 lettered copies. Folio has been bumping up the number and prices of its limited editions in the last few years. Some of them are exceptional but I passed on the Folio Neuromancer. The signature was on a glued-in card, the case strikes me as ugly, and it seemed to be perfectly standard Folio binding, printing, and paper quality – quite nice but not $600 nice. Last week Folio released a non-limited version for a more reasonable price.

Centipede Press intends to release its own limited edition of Neuromancer next year with illustrations by the wonderful artist Dave McKean. And there will undoubtedly be new releases and perhaps more limited editions when the Apple TV series appears.

Neuromancer continues to shape our perception of the technologically saturated world. It captured the anxieties of the 1980s that have only intensified in the modern era of surveillance capitalism, staggering inequality, and the blurring of lines between the human and the machine. In many ways, we’re living in Neuromancer’s vision of the future.