Last week I gave you thumbnail recommendations of five novels written between 1961 and 1986 that make me swoon.

Here are five more spanning the period from 1989 until the early 2000s.

THIS WEEK

The Remains Of The Day, Kazuo Ishiguro (1989)

Poor Things, Alasdair Gray (1992)

Kafka On The Shore, Haruki Murakami (2002)

Cloud Atlas, David Mitchell (2004)

The works of Cormac McCarthy

Catch 22, Joseph Heller (1961)

One Hundred Years Of Solitude, Gabriel Garcia Marquez (1967)

The French Lieutenant’s Woman, John Fowles (1969)

A Confederacy Of Dunces, John Kennedy Toole (1980)

A Perfect Spy, John Le Carre (1986)

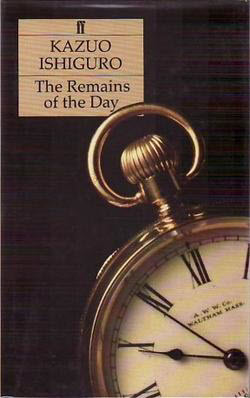

The Remains Of The Day, Kazuo Ishiguro (1989)

Kazuo Ishiguro was born in Japan but grew up in Britain. The Remains Of The Day is told in first person by an English butler about experiences at a large country estate in the 1950s and during the years leading up to World War II. The novel explores the cost of blind devotion and the sacrifices we make in the pursuit of duty. As you share the characters’ experiences, you’ll ponder what truly matters in life and the choices we leave behind.

That’s part of what draws me, but I’m also drawn to the extraordinary writing.

Every single sentence sounds like it would be appropriate for an English butler. The author never stumbles or loses control of the narration. When you read it, you will hear an English butler in your head.

Ishiguro’s other books are also splendid, especially the two recent science fiction novels Never Let Me Go and Klara And The Sun.

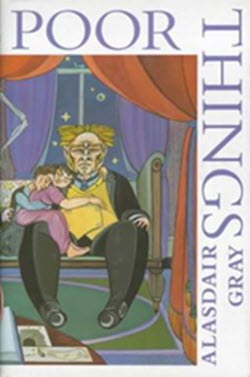

Poor Things, Alasdair Gray (1992)

Poor Things is another metafictional novel that is even more enjoyable now that it has been adapted into a quite different movie, featuring a performance by Emma Stone that absolutely must be seen to be believed. (There is sex. There is quite a lot of sex. Do not go into it unaware of the sex.)

The movie tells a straightforward story, at least as straightforward as a tale can be that weaves together Frankenstein, gothic steampunk, fantasy and mythology, black comedy (it’s frequently hilarious), an alternate world that isn’t quite Victorian England, and sex. Look, I just want you to be prepared for what she does with the apple, okay?

The book, though, is quite a different affair. In an introduction, the author Alasdair Gray claims to have found two documents: a memoir-like manuscript by Dr. Archibald McCandless; and a letter from Victoria McCandless disputing her husband’s account. The author adds footnotes with historical context, explanations, and commentary.

It’s all fictional but elaborately presented as fact. None of the narrators are reliable, including the author. The novel explores themes of gender identity, class struggle, and the ethics of scientific advancement. It is almost certainly unlike anything else you have ever read.

Kafka On The Shore, Haruki Murakami (2002)

Haruki Murakami’s novels are impossible to summarize, spanning science fiction, fantasy, crime fiction, and magical realism. I’ve read many of his books and could just as easily have chosen The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle for this list.

Kafka On The Shore tells the seemingly unconnected stories of two lost souls, a teenage runaway named Kafka Tamura and an old man with a mysterious ability to talk to cats. The stories converge, the lines become blurred between reality and dreams, and there is a touch of the uncanny and supernatural. On the one hand the story is deeply personal and hinges on hidden family ties and the search for family connections. On the other hand, there are raining fish, interdimensional portals, and a metaphysical entity residing in a large stone.

You can tell if it is or isn’t for you, right?

Cloud Atlas, David Mitchell (2004)

Cloud Atlas is literary magic. There is nothing like it.

The novel consists of six main stories, each with its own distinct era, genre, and narrative voice. These stories are introduced one by one and are deliberately interrupted mid-way. After the sixth story is half-told, the novel reverses direction, completing each narrative in reverse order, from the most recent story back to the first one. There’s a Pacific journal from the 18th century, letters written by an ambitious composer in the 1930s, escape from a futuristic Korea, and a folktale of love and betrayal in a dystopian far-future after civilization has collapsed.

The individual narratives aren’t entirely isolated. Each story is subtly connected to those before and after it. Characters from one story reappear in another, sometimes in vastly different roles. Books, letters, or recordings left behind in one time period are discovered and read by a character in another. A recurring birthmark links individuals in different timelines. There are hints of reincarnation and themes of power struggles, exploitation, the yearning for freedom, and the enduring nature of the human soul.

It is a very literary book that probably seemed unfilmable. The Wachowskis and Tom Tykwer kept its essence but translated it into the language of film, making the book and movie into fascinating companions. The movie cuts among the criss-crossing stories more frequently and emphasizes the connections across timelines using visual motifs and casting the same actors in multiple roles. Actors like Tom Hanks, Halle Berry, and Hugh Grant each play six different roles, occasionally almost unrecognizable – and yet subtly reinforcing the themes of of reincarnation and interconnectedness.

Like many people, I didn’t discover Cormac McCarthy until the Coens made the movie of No Country For Old Men in 2007. The movie is faithful to the book in most ways, drawing much of the dialog straight from the page. I went on a journey, next reading The Road, a sustained exercise in shades of black and grey unlike anything I had ever read. Then back to the Border trilogy as I became more familiar with McCarthy’s writing style and began to appreciate what a long shadow he casts over modern literature.

I have literally never had a reading experience like the night I first read the “legion of horribles” sentence in Blood Meridian. I stopped in disbelief, straightened up in bed, read it again, shook my head and smiled, and went back a couple of pages to have the pleasure of encountering it again. Here’s my love letter to Blood Meridian, the first book I mention when people ask for my favorites, the peak of my collection, my favorite book to re-read.

McCarthy’s books can be challenging and harrowing. There is darkness and violence but there is a surprising amount of humor around the edges. At some point you will get to Suttree, a less well-known novel about a young man living on a ramshackle houseboat on the Tennessee River in 1950s Knoxville. There are frequent laugh-out-loud moments in Suttree and I can guarantee you will never look at a watermelon patch the same way after you read it.