Ray-Ban Meta smart glasses have cameras in the frames. You can take pictures and shoot videos, then upload them. It’s a fast and convenient way to record a moment without pulling out your phone. You can post the images to Facebook or Instagram, or ask AI questions about them.

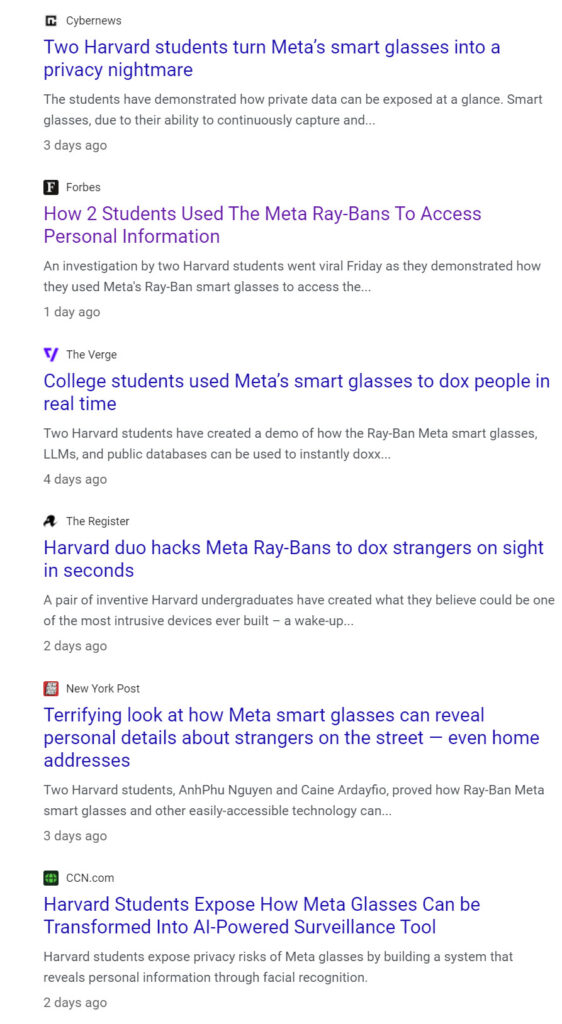

Last week two Harvard students got viral coverage of a project they put together using Ray-Ban Meta glasses. They streamed live video to Instagram, then ran it through publicly available websites. When results were relayed back to them, they were able to walk up to strangers and know their names and other biographical details.

The students titled their paper: “The AI Glasses That Reveal Anyone’s Personal Details—Home Address, Name, Phone Number, and More—Just from Looking at Them.” Because even an academic paper gets a clickbait headline in 2024.

This is low-hanging fruit for journalists starved for topics to write about and eager for attention. “Utterly dystopic.” “A new age of surveillance.” “A privacy nightmare.” “Terrifying.”

Well, no, I don’t think so.

Two things are wrong with the dystopian “invasion of privacy” spin on this project.

One: The glasses aren’t a necessary part of this operation.

Tech journalist Mike Elgan put it this way:

The setup “feels” like this: “Smart glasses can invade the privacy of anyone you’re looking at.”

What’s true is this: “Smart glasses have a camera. *ANY* camera can be used to invade the privacy of anyone you’re looking at for reasons that have nothing to do with smart glasses.”

Elgan’s article lists the specific online tools used for the trick. The students grabbed faces from their live stream video, then uploaded the faces to services that do facial recognition. Once they had a name, their software then checked a database with publicly available information about people.

A clever hack! It’s one that could be done with any camera. It is being done. It’s being done routinely. As Elgan explains, it’s a modern variation on “hot readings” by fake mediums and psychics in circus tents in the late 19th century. It’s being done today by governments, law enforcement agencies, and private companies.

Because there’s something you should know already: there are cameras everywhere. It’s not just the ubiquitous cameras in our pocket (or on our face); it’s not just the ones you notice when you look up in stores and airports. Those are only a tiny fraction of the places your face is being recorded and analyzed by facial recognition programs.

I wrote an article five years ago about how many cameras are in our modern world and what they’re used for.

You see some of the cameras – at street intersections and on the sides of buildings, for example, and on the ceilings of virtually every retail establishment. There are oh, so many more cameras! The DEA and ICE have embedded cameras in street lights and those orange traffic barrels. Some billboards have integrated cameras. . . .

Taylor Swift’s security team installed cameras with facial recognition software inside the selfie booths at her Reputation tour. The same company has supplied cameras “at Nascar tracks, Daytona Beach’s luxury mall and at the Redskins’ FedEx Field. Soon they will be at Minor League Baseball stadiums, and ISM hopes to integrate them into ‘smart cities’. Already, the company’s screens have captured engagement and demographic data on over 110 million event-goers at more than 100 venues, according to their website.” . . .

Retailers are contracting with facial recognition providers to log people’s faces. . . .

Facial recognition data is being shared widely with law enforcement and government agencies. . . .

The price has dropped so much on license plate readers that they’re being installed everywhere. EFF: “Automated license plate readers (ALPRs) are high-speed, computer-controlled camera systems that are typically mounted on street poles, streetlights, highway overpasses, mobile trailers, or attached to police squad cars. ALPRs automatically capture all license plate numbers that come into view, along with the location, date, and time. The data, which includes photographs of the vehicle and sometimes its driver and passengers, is then uploaded to a central server.” Private companies like Vigilant Solutions have compiled facial recognition and license plate recognition databases (“over 5 billion vehicle detections”), and share that data nationwide with thousands of agencies.

Two: It’s not an invasion of privacy because we have no privacy.

It is long past time for us to get over being shocked that we have no privacy.

This quote also comes from an article I wrote five years ago. Nothing I wrote about then was new – that was the point, it was already a long established industry.

Assume there’s a company that methodically scrapes information from public records – drivers licenses, voter registration, property rolls, census and change of address records, birth certificates, marriage licenses, bankruptcy records. It combines that information with everything it can collect from social media sites or buy from private sources – bank card issuers and financial institutions, retailers, health care and insurance providers, whatever is available.

The company accumulates and distills that information into individual profiles, and keeps adding to each profile as more information comes in. It’s got your name and address. It’s got your email addresses and your phone number. Oh, and a few other things – these are just examples of the thousands of data points in an individual profile:

“Age, race, gender, height, weight, marital status, religious affiliation, political affiliation, occupation, household income, net worth, home ownership status, investment habits, product preferences and health-related interests.” . . .

There is not just one company. There are more than 4,000 companies in the business of compiling personal information into profiles that are sold to advertisers and marketers.

The data broker industry is estimated to be worth at least $200 billion.

Data brokers are unregistered, unregulated, and untracked.

You cannot find out what data a broker holds on you, how a broker got it, or how it is used.

Many of the data brokers are enormous companies with billions of dollars in annual revenue, but you’ve never heard of them. They are thriving in the shadows.

In 2013 Google Glass failed in the market. One reason was that people hated the idea of a camera taking pictures without their knowledge, but the more important reason that Google Glass failed was that they looked funny and we weren’t used to seeing people with tech on their face.

Ray-Ban Meta glasses don’t look funny. They look exactly like normal Ray-Bans.

And we are ten years further in the era where picture taking is universal, continuous, inescapable.

Privacy? Surveillance? The time to worry about that has long passed. Now it’s simply a part of modern life. We could ban smart glasses tomorrow and it would have exactly zero impact on the data collection that is deeply embedded in our modern world.

A couple of years ago I wrote a fantasy about a hypothetical law that could restore privacy. Oddly enough, that law has not yet been passed and my phone has been quiet – I haven’t had any trouble fielding off inquiries about it.

The Harvard students did clever programming. I hope they get a good grade. But it’s not new and they didn’t violate any social norms. Your life is an open book and your “private” details will never be private again – the cat is out of the bag, the horse has bolted, the genie has been released from the bottle. It’s time to get used to that idea and embrace cool tech that builds on it because there’s literally no alternative.